Find this helpful?

This is just a small sample! Register to unlock our in-depth courses, hundreds of video courses, and a library of playbooks and articles to grow your startup fast. Let us Let us show you!

Submission confirms agreement to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

Already a member? Login

AI Generated Transcript

Ryan Rutan: Welcome back to another episode of the startup therapy podcast. This is Ryan Rotan from startups dot com. Joined as always by my friend, the CEO and founder of startups dot com. Will Schroeder. Will, we're in the business of just being right all the time, right. Startup companies are nothing but a collection of the right decisions, the right hires, uh you know, the, the right business model, the, the right strategic moves. Like how often do we actually get to be wrong in this gig?

Wil Schroter: Uh All the time you got, we're in the business of wrong. That's at an epic level, which is hilarious because we lamb based ourselves, we land based other startups, uh even, you know, investors, et cetera for being wrong. Yeah. And it's like that's the business that we're in now. It's different. If we were talking about public companies that have been running forever, they're not allowed to be in the business of Rob. I mean, to the extent that they should have had their stuff figured out by now. So it's a little bit different. So when they miss earnings or, or when they go off the rails, maybe the culture of wrong doesn't make quite as much sense for them because they

Ryan Rutan: release a new recipe for Coke, you know, things like that. Right. Like they, they can make mistakes but it's, it's let us at the fundamental level. Right.

Wil Schroter: But where we're at, where we're figuring out everything for the first time where every single thing is a variable, we actually don't have constant yet. I would argue in a big company. Big Fortune 500 that's been around forever. They actually don't have a lot of variables left. They pretend like they do, they do big strategy meetings, et cetera. But, but if they get crazy that business changes 10% in 5 to 10 years, all the hard stuff. And I've argued this before was done generations before anybody that's probably still there. That's when it was all variables. We're in the business of all variables. And yet as founders, we get so hung up on the thinking that we can have all the right answers. It's kind of hilarious. So I thought what would be cool today? Let's walk through all of the things that we mistakenly let's call it foolishly foolishly think that we have the right answers to and we couldn't possibly have the right answer. And by the way, this will let a lot of people off the hook both personally within the organization. So uh right in, in your mind of all the things and there are many things uh where do we start

Ryan Rutan: here. Yeah, let's start at the very beginning. Let's, let's start with the business idea itself, right? Uh This is often where we go off the rails, right? Uh But to your, to your point before we continue with this, uh, there should be a whole lot of sighs of relief during the, the listening of this episode. Uh, and, and you said this before we get started today? Well, but I think this is gonna be a really interesting one where founders can share it with their teams. Uh because we're going to talk a lot about how and why this is important, not just to the founder but how this permeates the entire team and how it impacts performance and a lot of other stuff. But yeah, I think that if we want to look for one of the places where not only is it nearly impossible to get it right from the beginning, a lot of founders get caught up with trying to do exactly that and they spend way too much time, you know, uh on the whiteboard or on the engineering bench or wherever, trying to perfect and get the business idea perfectly right before it ever sees the light of day. And we've been over this ad nauseum. That's not how it works, right? It just isn't how it works and until it sees the enemy, uh we're never going to know how well it performs.

Wil Schroter: I get to the point right. To tell founders, don't worry, it actually kind of doesn't matter what your idea is right now. It's just raw clay right now. Right now, your, your idea is raw clay and no matter how much you think, it's the right idea. It's the perfect idea. It's going to wind up being horrible and not because it's a bad idea per se. But to your point, Ryan, because you haven't talked to anybody about it, you haven't tried to sell it to somebody, right? Your steak tastes terrible until somebody pays a premium for it. Right? Everybody spits it back out. Guess what? It's a shitty steak. And so I, I think that what we get so hung up on and, and I think we've done episodes about this too where, you know, people get hung up on their idea and they don't launch because they don't think the idea is right and perfect yet. And we try to tell them it kind of just doesn't matter. You actually can't be right at the formative stages. I don't think, I don't think we've ever seen anybody come out of the gates and nail it the first time and, and if they did it was the powerball odds that

Ryan Rutan: it was pure luck, right? Everything else starts in like you said, it's some Ray uh Raw Clay format and we just have to work our way through forming and forming and reforming and showing it off, right. This is not again, something that we do in a vacuum, right? If you're just reshaping the clay in a vacuum, I hope you like playing with clay because that's what you're gonna spend your time doing. Uh Nothing is ever going to solidify. Nothing's ever gonna take final or closer to final form that becomes the product of the business that we actually want to build. Right. There's no version of us quietly and secretly doing this somewhere. Uh And just magic landing on the right formula for the idea. Are we suggesting that the second you have an idea, you just start plastering it all over the place and running around town and telling everybody it's the best thing ever. Um Maybe, I don't know. Uh Probably not exactly that either, but we're certainly not saying, hey, just keep this a secret forever and try to figure out how you can become exactly right about what this idea is just not the process.

Wil Schroter: You know, something that's really funny about everything we talk about here is that none of it is new. Everything you're dealing with right now has been done 1000 times before you, which means the answer already exists. You may just not know it, but that's ok. That's kind of what we're here to do. We talk about this stuff on the show, but we actually solve these problems all day long at groups dot startups dot com. So if any of this sounds familiar, stop guessing about what to do. Let us just give you the answers to the test and be done with it. All this is part of accepting being wrong. And I think for most of us coming out of whatever career we came out of whether it was academia, which is 100% based on being right, the entire thing is based on how right you are usually the first time by the way. And so we get indoctrinated there, then we go to a job again, typically an established company where, where the processes have already been figured out, the people have already gone through the versions of wrong. They, they turned their variables into constant and we're graded on being right. So we come into this for the first time out of either of those uh paths which are pretty common. Most people are coming out of it doesn't occur to us that we can start with. I have no idea. I have no idea in our minds. We know we have no idea. We've been conditioned to be afraid to tell anybody this, to say to anybody. I think I'm wrong. I'm the ego, the

Ryan Rutan: ego steps right up and says, like we have to be right here or this won't continue. I think that's a big part of the problem is that people assume that if at any point, somebody else tells them this is wrong. The fragility of their own feelings around the concept is so high that it's just gonna collapse and then not gonna continue. Right. We, we use and it's a terrible one we say, like, you know, people are afraid to find out their baby is ugly. Right. Well, you kind of have to go through that process. Here's the good news. Your baby will change very quickly. It'll change a lot faster with feedback. Right. They grow fast and, you know, give it proper treatment. They'll turn out great. Uh It's, it's if we just, you know, lock it away in the closet and hope that it turns into something else. Not a good

Wil Schroter: place, a metaphorical

Ryan Rutan: baby businesses. Yeah, it's a metaphorical baby folks, metaphorical

Wil Schroter: baby. So one of the places you, you, you touch on this and I just want to expand on it where we have this idea. We're afraid to be wrong and more so we get told we're wrong by the wrong person. Yeah, for sure. So our rich uncle comes to us who killed it in real estate and says your mobile app idea is terrible because you don't have good operating margin. He doesn't understand even what that means for our business, right? But because it meant a lot in his business, he's just projecting on, on us and we look at that and say, oh my God, I guess I have to change things. I'm wrong. No, no, he's the wrong person to be wrong. Your inputs are wrong. You talk to an investor an investor says you're going after the totally the wrong market. This is the right market to go after. Cool investor person. Do you live in this market? Are you a customer from that market? Will you buy from us in that market? No, no, no, you're the wrong input.

Ryan Rutan: Are you also going to hand me all of the money to go test that market that might change that, that might change my mind a little bit. I might say ok to that,

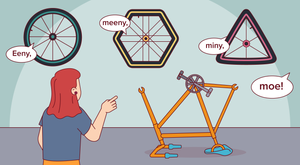

Wil Schroter: but I think that we are so used to seeking out these right, these definitive answers, especially for things that are so unknown. Like our ideas that we lose our stuff, we totally misunderstand and miscalibrate how we should be approaching this. If we are trying to invent, if we are trying to create something out of nothing, we have to be wrong. We have to be wrong many, many, many times and, and I would argue, I'll take this the other direction. If we don't push hard enough to be wrong, we're screwed because then we never really know what the potential. I I'll give you an example, pricing it. Whenever we get into pricing, we say, wow, should we charge this? Should we charge this? Should we charge this? And we always come back to the same conclusion because we've been at this for a minute. Let's charge everything. Let's try every possible combination. Let's try one time. Let's try lifetime. Let's try recurring let's try every possible combination because none of us knows. We don't know. Our customer knows.

Ryan Rutan: Yeah, they, they know what they'll pay and they know how they'll pay. They know when they'll pay, they know why they'll pay

Wil Schroter: in, in, in our first five or month worth of customers may give us the wrong data. And what we're saying is all we know is that if we try enough things over a long enough period of time, fortunately, hopefully the answer will appear, but there's no version, we can whiteboard it to death and come up with the answer. It just doesn't work like that.

Ryan Rutan: But I have a 64 Tab Excel spreadsheet that I've been working on for 96 weeks that is going to give me the optimized price. And I've

Wil Schroter: never, I've never seen a business succeed because they lean canvassed the hell out of it. Don't get me wrong. I like lean canvas. It's actually, it's actually a very logical approach. Uh So, but what I'm trying to say is that was never what built the business it was. They lean canvassed it and maybe they skipped a couple missed step. They would have otherwise made with less research. Always a good practice. But ultimately, until they got the idea out there, until they saw what it took and by the way, getting the idea out, there's one piece of it and we'll talk about other pieces like hiring the team around it. The marketing around it and all these other pieces, uh You're barely at the 1% of your progress bar on, on how you're supposed to look at this. So if we have the least information we've ever had on this idea and we're trying to be right about it. It's goofy.

Ryan Rutan: It is, it is like you have, you have almost no data and yet what you're going to do is spend time analyzing what little you have and trying to come up with a long ranging conclusion that drives the business, right? Like we're not suggesting not to think about it, right? We're not suggesting not to analyze it, but we are suggesting to, to put those things in proper balance, right? All thinking with no action is not going to help you, right? Assuming you have to be right before you begin, also not going to help you, right? All of these, all of these areas where you make an assumption and you test it, you find out you're wrong are simply the railroad ties that we're going to lay the tracks to being right on, right. That's the way this goes, but have to do that. You have to go through being wrong. So you can figure out what right actually looks like because it can't be defined from the beginning, right? That's the thing if I asked you. OK. So what does being right actually look like? How do you know that you got the right business idea. They'll have no idea. Right. It's crickets because how could you possibly? And yet you're trying to figure out and you're trying to somehow magically arrive at this unknown destination and then somehow realize that you've gotten there. So stop wasting your time trying to be right. Go ahead. Make some mistakes. Be wrong. It'll be ok. It's a promise.

Wil Schroter: Right. You'll be fine. The next thing we're gonna do a, a, as a business after we beat up this idea and you know, try to pretend like we're right is we're gonna bring somebody else on, that's not us to try to help us grow this thing. And that could be a co-founder. Do, do they know what's right? Of course not.

Ryan Rutan: Is that where it happens? Oh Damn. Which

Wil Schroter: is, which is where things get even more challenging because the only thing more confusing than being by yourself and being wrong is adding another person who thinks maybe they should be right too or another person after that escalate the confusion.

Ryan Rutan: I talk about this all the time when people are like, I just need a co-founder. Why? Well, I'm just really not sure of my decisions. I'm I'm not sure if I'm right about this or right about that. And I'm like, and so you want to add another person who has the same level of confusion to the mix and somebody you think this is gonna make it easier and they go, yeah, that doesn't sound like what I was after like, well, that's what you're probably gonna end up with.

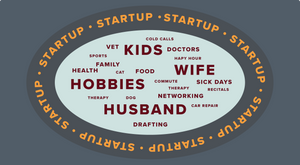

Wil Schroter: You want to multiply the problem and look, it, it does help to have other voices. It does, it does help to have other inputs, experiences, et cetera. But here's the part that we're missing. We have to understand when we're making these hires. Number one, the probability that we made the right hire to get that voice is so incredibly low that it's almost laughable. And why is that few reasons? Number one, when we go to hire, let's say we're looking for a co-founder or we're making our first hire. We fundamentally have the fewest resources we're ever going to have to source that talent. Well, sometimes we get lucky. Sometimes we have a coworker that we used to work with that actually has the skill set, et cetera we can bring on. And I would say that that's fortunate. I also say it's rare more often than not. We're out there scouring for two things, strangers and strangers who will get paid next to nothing to work for us. Two variables that don't work in our favor. So here we are thinking, I've got to make the right hires. I've got to put together the right team. What are the chances you're gonna pull that off? Pretty much, very,

Ryan Rutan: very slim, right. It's, it's, it's around as close to the, the same odds as if I spend a lot of time thinking about it, I'll get this. Right. Right. Which is to say that number one, your odds of getting this right, are extremely small. Your chances of improving your odds by spending a lot of time or analysis or whatever else is that you think you're gonna do also extremely small. Right. You've brought this point up before many times. Well, which is at some point, we just have to take the step, we have to make the hire and we might make a mistake. There, chances are we will make a mistake and then we'll correct for it right back to back to where we started with this. It's ok to be wrong. It's ok to be wrong about the hire. Try to be as right as we can, uh, but be willing to admit that we were wrong about this. And I think that emotionally, this one tends to be almost as hard, if not as hard as being wrong about the idea itself. Uh, because now we're, we're introducing someone else's human emotions and their dignity into the mix and our own ego saying, but I, I wanted to have picked the right person, but now I've got the wrong person right. We talk about this in, in startups a lot, but it's, it's, you know, higher, fast, fire, fast, it sounds horribly calloused. Uh, and to some degree it is, but it's also very necessary. We have to be able to admit when we're wrong about the person we brought on and correct for that. Maybe that's training, maybe that's realigning the role, maybe that's realigning expectations, but sometimes it just means parting company, um, and being willing to admit that we're wrong about it for their good and for our own.

Wil Schroter: I agree. I, I think that, uh, in, in my history having hired over 1000 people in my career, I can tell you this, I've learned very little about how to hire people, but I've learned a hell of a lot about how to fire them. And, and what I mean by that is not my favorite part of it. I've learned that no matter how many interviews I do, no matter how cool questions I ask or background checks that I do. It never really tells the full story. I would argue that you can take out the false positives pretty quickly, right? Like you can look at, oh, ok. That, that is an obvious holy cow. Don't, don't go down down that road again. Um, here's a silly one, but I think people can relate to it when you ask somebody. Is there anything you like about your last job? And they spend 20 minutes just going in an absolute tirade about what an A hole their boss was. Chances are, there's probably a problem there like the, the people that do that not across the board, right? Tend to do that everywhere else they go. Right. It just for what it's worth. It's not. Oh my God. If they ever do that, I'm done. But generally speaking, when I see that kind of behavior, especially if you're in an interview and you're not even aware that you probably shouldn't be doing that. Usually a pretty good indication that that things aren't gonna go well. And there's a few of those, there's a few of those flags that, you know, that I can put out there. But short of that, you don't really know who this person is until they get into this specific role with this specific team at this specific moment in their lives. Remember the other side too is that's a huge variable. You got somebody coming in and they just had their first kid. Wonderful. Guess what? They're not the same person. They were 10 minutes ago when they didn't have that kid. You and I are right. We saw that firsthand, right? You have a whole new set of, of requirements and distractions, et cetera and most of our staff has kids, right? And so it's not like it's something that, that we don't hire for, but we're aware of, you know, some of the challenges there. Now that said, what I'm really talking about is how things have changed for them. So they're coming into this job saying, oh, it's just gonna be like the last few jobs that I had when I didn't have a kid. It is not another variable that gets dropped into the mix and we're pretending like we can solve for all these in a, in a 60 minute interview. Can't happen, actually can happen. You

Ryan Rutan: touched on a couple of things that I think are really important. One, you know, their individual circumstances may be changing to. We're a brand new business, right? Very little is figured out here. And so even if the objective evidence says this person's really good at a role that looked a bit like this at a company that might have looked kind of like this. It's not the same playing field, it's not the same stage. So even if they were a rock star, somewhere in the past, doesn't mean they're gonna rock this stage. And we have to be very careful about making those assumptions, right. If we put them into exactly the same situation, we would expect them to get nearly the same results that's not gonna happen here, right. The, the chances that this role is exactly like the last role, very, very small, even going corporation to corporation where as you've said, 80 to 90% of the variables are eliminated and we're operating in a relatively clear and static environment, that's not the case. So when we introduce the fully variable situation, that is a startup company, being able to pretend that we're gonna do some sort of calculus mix with crystal ball and figure out who's exactly right for the role, it's a great waste of time

Wil Schroter: I watched this happen in real time. Uh in my first business, once we got to the point where we were thinking about going public, we had to staff up with, with adults and we wanted to go out and find a CEO S. Yeah, we, we wanted to find uh go out and find a CEO uh that had uh checked all the boxes. Um Ray

Ryan Rutan: hair, how to tie a tie, a

Wil Schroter: tall white male with gray hair. I mean, at the time this literally like, like, like what people were inventing is, is a whole different time. Thank God. So we, we find this guy and uh and I won't name his name or anything else like that, but um probably the most perfect resume. You could have top Ivy League, top consulting company, top public company, top public company after that, like he was the guy and he was big three tattooed

Ryan Rutan: on his neck. Yeah.

Wil Schroter: Yeah, exactly. He, he was, he was looking for a company that was just about to go public so we could like, you know, negotiate a big stake in, in cash in, right? Um This was in the nineties where there weren't as many of those as there are now, there weren't as many venture funded companies. Um So we had a good opportunity to find something like this. So we ended up uh getting to come on board and at first I'm enamored because again, I'm like this is the business Yoda that I've been looking for. Actually, I'm not kidding. He would sit back and tent his fingers and talk to me over his tinted fingers about business strategy. And all I thought to myself was you are a caricature of what people think a, a president or CEO of a company. It was hilarious. Right. But, but here's the best part. So he comes on board, he checks all these boxes and we're a very large agency at this point. So at this point, like, like we're looking to get massive, massive clients, we need 50 or $100 million client wins in order to move the meter all for us and tell our story. This guy is as connected as it gets at all the top levels, all the boards, everything. And so after like an uncomfortably long time, like two months, we're like, bro, are you gonna start making some of those calls to some of your buddies? And he was like, yeah, I just don't know if the timing is right? And then I'm like, you know, we're an agency like this is all we do. Like business development isn't like you, your sort of job, business development is your job, right? And he didn't understand that. And he wanted to know like, like, like what our catering service level was like, he wanted to know like if, if you only got six weeks of vacation he wanted and we're like, what are you like he and the other guys haven't taken a vacation 10 years. I was like, where do you think you are? So here we had locked in all the variables that we thought were the perfect candidate into his credit, super smart guy, right? In the right environment, you know, amazing.

Ryan Rutan: Obviously, it performed well up until that

Wil Schroter: point, we didn't calibrate the one variable that mattered. Our variable, we were the variable, right? Working in this business. So I love it when people poach people out of big co and, and they're like, oh yeah, we got this amazing person. I was like that person ever worked in a startup before. Ain't the same thing. Ain't the same thing, right? I mean, so, so you see it, you know what I mean? Yeah, for

Ryan Rutan: sure. No, it's again like I, I, I think the ability that we have to get this right ahead of time uh is small. I mean, that was, it's hysterical and it's, and it's kind of the pinnacle example, right? Like you're probably not, most people that are listening to this probably aren't looking to hire a CEO to go public. Uh They're like, how do we hire our first customer service rep? It's the same problem problem. That's exactly, that's the point I want to get to is that while this may sound like an outlandish and, and crazy example, this applies all the way down the chain from top to bottom the amount of ability you have to, to game this to thumb the scale to get this right is extremely

Wil Schroter: limited. And I'm saying if that's the best case,

Ryan Rutan: right, that's the best case where you have tons of objective data, long track record, right? Probably tons of references and tons of referenceable wins, victories, statements, lots of public information around this individual. When you're about to go hire your first hire who just got on linkedin yesterday as they're looking for their first job. Pretty different story. So don't try to apply because even when all the information is there, it still doesn't work to your point. Uh And when we have very little information, this should help us to very quickly, right size, our approach to this, which is there's gonna be some dice rolling here, folks get OK with it, right? Let's

Wil Schroter: talk about that, Ryan. Yeah, you are the chief dice roller because because you're, you're in charge of marketing, right? As our CMO you are more used to rolling dice and, and running into the abyss than anyone because it's so integral in what you do. That's what we do. How often from the marketing side are people getting marketing?

Ryan Rutan: Right? I mean, at the at the early stages, almost never. Is it even possible? Not without some luck, right? It's kind of like you said before, right? Like you, you may end up picking a channel that has some degree of success for you you end up getting it to work out. Does it usually work out? And is there, are we saying the words R O I and week one month, one generally not, right? Like we're, we're, we're testing things. We're, we're constantly looking for why we're wrong. I think that, you know, this is one of those places where, and it took me a long time to get here, but once you get there and it's like you adopt that, let's figure out why we're wrong. Like here's what we think is gonna work. Here's what we're gonna go try. Here's why we're probably wrong or let's go find out why we're wrong and then we make corrections, we make adaptations. You know, I think the, the one, the one saving grace to the fact that that marketing is often wrong and starts wrong and continues wrong is that we do get to make corrections and we see the objective outcomes of those much sooner. So while we tend to be wrong more than maybe anybody else in the entire organization, we have the luxury of finding out how to get closer to right, faster than anybody else as well. So I think that there's, there's a little bit of solace to be taken in that, right. Like I can run some ad tests and find out within a couple of days if I'm on the right track or not, the wrong hire that could take months or years to find out that we didn't get exactly what we wanted. Right. Business idea sometimes. Right. Like, we know, we know people who have been working on something for 10 years and finally they're like, you know what? I just, it probably wasn't the right idea to work on for whatever reason. Right. So the time frames can be so protracted. And I think that's again, like the one, the one small piece of solace that I can take uh is knowing that the time frames on being wrong tend to be at least a little bit shorter and I can get right faster.

Wil Schroter: That's true. And a lot of people are saying, hey, I want to start with Facebook marketing. I wanna start with social. I want to start with, you know what, whatever their channels are that they think uh they should get into. And the question is always the same and, and Ryan, you being in this as a CMO uh me having come from an agency world and had this conversation about a billion times also with startups is they wanna know where can I be? Right? My answer is always relatively the same. My answer is always your job right now is to set it all on fire and find out where it starts burning less. That's it. They set it on fire because I want to put that mental image in of there's no version where you're just gonna invest out of the blue and all of a sudden it hit exactly the right channel for exactly the right customer with exactly the right message and, and all the conversion metrics, all the, at the same time you might get a few right. And, and you were a little bit good, mostly lucky, but there's no version with in marketing, especially at scale where you actually know the answer. You don't, you can't. That's sort of the point which is why going back to this culture of wrong, we have to be able to sit down with our marketing budget, our team, our agency, et cetera and be prudent about it. I know, you know what I know, there's no way to get this right, especially out of the gates. How can we test so that we can learn to be less wrong. Our marketing, our growth is about being less wrong. A very different approach in how you look at the

Ryan Rutan: business. Yeah, for sure. And I, and I think if we don't look at it that way and, and, and I think you just said something that's important and we can continue with that, which is the this culture of being wrong, right? So this extends beyond the idea, this extends beyond the hires, this extends beyond uh uh marketing. Uh this permeates the entire organization, right? When we adopt the and embrace the ability to be wrong and understand that that is just part of the process. I things will start to move much, much faster, right? Because if we look at the, at, at the other side of that coin, right? Where we set this expectation that, you know, uh you gotta come in, you gotta be hard charging, you gotta drive results, you gotta, you know, do all this stuff at the beginning and we basically eliminate any wiggle room or perception that they can be wrong. We're all, but determining the outcome here and it's not a good one, right? Because the idea that they come in on the first day and they're right, uh really small and if they don't feel like they're allowed to be wrong, the, the idea that they're going to somehow go through all the required permutations without ever being wrong and get us to that place. We want to be, it's zero,

Wil Schroter: right? It's dangerous culture a

Ryan Rutan: 100% and it spreads fast. Right? Doesn't have to be from direct experience. You've talked about this before. If we get uh punitive with somebody over being wrong, right? Doesn't just impact that person, right? Everybody on that team or in that slack channel or in that meeting or on that email, who sees how that person was beat up, beat down, denigrated in whatever way for being wrong. Everybody else is gonna take notice of that and they're gonna go, oh, shit, I can't be wrong either.

Wil Schroter: Well, let's define that wrong because you know, I, I think you and I see 22 different versions of it. There's a wrong where you're just straight up lazier and competent that, that actually probably does deserve, you know, whatever response is coming, of course, by all means temperate. But, but that's different. But what you're talking about isn't that? No, no, no, just straight up did something wrong again, whatever. I'm

Ryan Rutan: not talking about negligence or dereliction of duty or even making a mistake. Right. Because I would, I would, I would put all three of those things in a separate category, being wrong, assumes that you had something that you were intentionally going after in the first place, right? That you, you had some level of an assumption, right? There was a hypothesis there and you, it proved to be wrong, right? If you're just running around wildly without hypothesis, you're not wrong because there's no way to be right. You're just negligent at that point,

Wil Schroter: you're just negligent. Right. Right. Right. And, and I think that what happens is at, at the top, at the leadership level, if we're sitting on the white board and the whole team is arguing about who's right about some pricing decision. Here's what I learned long ago. And I think this will, this will help some folks uh kind of diffuse things a bit when we get into a situation where things are getting heated. My default answer is always this. Why don't we agree that I don't know the answer and you don't know the answer either. We'll argue about what our opinions are of what the answer could be. But let's take this off the table for a second as if we're arguing that one of us actually has the definitive answer. Right? Because we rarely do if we're saying here's what pricing could be should be. We're both gonna make strong cases for where we've seen a pricing scheme work in the past where other similar businesses have run the pricing scheme. But the truth is the truth is unless we run these pricing schemes and test them, no one actually knows and we won't know until we get it out there. And I think that's a culture that you can build where you can look around the team and you can set that tone and say, why don't we agree that none of us actually knows and restart the conversation from there. What do we want to test? What, what do we want to learn together, given different inputs and see where we can go? Now, here's what's cool about that. You start that at the leadership level and you start to say, look, um I've got imagine this a bit of humility that maybe just because I've got ac in my title, I don't actually have the answer and we start with that taking that humility and broadcasting it across the organization. Somebody has a, a big swing that they make, let's say on marketing and it doesn't pan out and our answer looks something more like, hey, there's no way you actually could have known if it worked. I appreciate the effort. I get what you were trying to do. Now, let's try to figure out how we can reload it and do it again. To me that's the right answer. Brow beating people over answers. They couldn't have possibly known to me is just weak. I think it's just, it's, it's a symbol of, of weak leadership. And I think it's a bad culture to build because here's what ends up happening. If we browbeat people over things, they couldn't have possibly known the answers to what do they do, they hide, they defend, they create every bad behavior that makes it so much harder for us to be effective leadership. We actually, we, we put a trap door in it. They

Ryan Rutan: did. Yeah, they start digging moats around all of their processes, all of their thinking, all of their right. It just, they just go into defensive mode, uh going back to what you said, right? When we run into this impasse situation where, where there's sort of two paths we can take. One is that we continue to argue to decide who's right and which path we're going to take. Um which we've already said there's no way of actually knowing which one of those two things is, right? When we say, hey, we don't actually know which one of these things is correct. Let's restart the conversation. Let's re stage the conversation and recast it in a way that allows us to decide which of these things are we gonna test first? Right. Let's look at our critical path as a business. Let's zoom back out beyond this decision. And let's say of these options that we have. Which one do we want to test first? Right. Which one makes more sense to test first? And we get everybody's thinking realigned to which of these are we gonna do now? Versus which one of these are going to do at all? Who's right, who's wrong? It completely changes the context and it allows us to move forward. Otherwise we just end up arguing, wasting a ton of time um to your point like having some humility. And I think having, you know, great leadership, I've seen plenty of great leaders just say like they may really truly believe and they may have more experience, they may have reasons to objectively believe their decision is right. Just say, let's try yours first. Let's just go with that first because if we spend all of our time trying to figure out who's right and never give ourselves an ability to be wrong, we're never gonna move forward at all.

Wil Schroter: So in addition to all the stuff related to founder groups, you've also got full access to everything on startups dot com. That includes all of our education tracks, which will be funding customer acquisition, even how to manage your monthly finances, they're so much stuff in there. All of our software including BIZ plan for putting together detailed business plans and financials launch rock for attracting early customers and of course, fund for attracting investment capital. When you log into the startups dot com site, you'll find all of these resources available.

No comments yet.

Start a Membership to join the discussion.

Already a member? Login